Dossier: Nuevas tendencias en los estudios homéricos

Socrates the Homer-lover as portrayed in Plato, Xenophon and Aristophanes

Abstract: Socrates is portrayed as a Homer-lover in Plato’s dialogues, both explicitly through his expression of love and respect for Homer since his childhood (Republic 595b9-10) and implicitly through his numerous Homeric quotations and references. Similarly, Socrates frequently uses Homeric references in the dialogues that Xenophon wrote to preserve his memories. The comparative study of these authors so far suggests that the historical Socrates did use Homer often in his conversation. However, we should also consider whether that portrait matches the Socrates depicted in Aristophanes’ Clouds, a more contemporary source than Plato and Xenophon’s works. This paper examines the portrayal of Socrates in the Clouds and argues that here, too, we can find a reflection of his love of Homer, especially in his invocation of the Clouds in lines 265-74. It will also consider how that portrayal of Socrates can affect our view of Socrates.

Keywords: Socrates, Homer, Plato, Xenophon, Aristophanes, Clouds.

Sócrates “amante de Homero” en Platón, Jenofonte y Aristófanes

Resumen: Sócrates es retratado como un aficionado de Homero en los diálogos de Platón, tanto explícitamente a través de su expresión de afecto y respeto a Homero desde niño (República 595b9-10), como implícitamente a través de sus numerosas citas y referencias. Del mismo modo, Sócrates utiliza con frecuencia referencias homéricas en los diálogos que Jenofonte escribió para preservar sus recuerdos. El estudio comparativo de estos autores hasta ahora sugiere que el Sócrates histórico se sirvió de Homero con frecuencia en su conversación. Sin embargo, también debería considerarse si ese retrato coincide con el Sócrates representado en las Nubes de Aristófanes, una fuente más contemporánea que las obras de Platón y Jenofonte. Este artículo examina la representación de Sócrates en las Nubes y argumenta que aquí, también, podemos encontrar un reflejo de su afecto a Homero, especialmente en su invocación de las Nubes en las líneas 265-74. También se considerará cómo esa representación de Sócrates puede afectar nuestra visión de Sócrates.

Palabras clave: Sócrates, Homero, Platón, Jenofonte, Aristófanes, Nubes.

Socrates is portrayed as a Homer-lover in Plato’s dialogues, both explicitly through his expression of love and respect for Homer since his childhood (Republic 595b9-10) and implicitly through his numerous Homeric quotations and references. Similarly, Socrates frequently uses Homeric references in the dialogues that Xenophon wrote to preserve his memories. The comparative study of these authors so far suggests that the historical Socrates did use Homer often in his conversation (Yamagata, 2012). However, we should also consider whether that portrait matches the Socrates depicted by Aristophanes, a more contemporary source than Plato and Xenophon. This paper examines the portrayal of Socrates in Aristophanes’ Clouds and argues that here, too, we can find a reflection of his love of Homer and considers how that portrayal of Socrates can affect our view of Socrates.

Plato’s Socrates

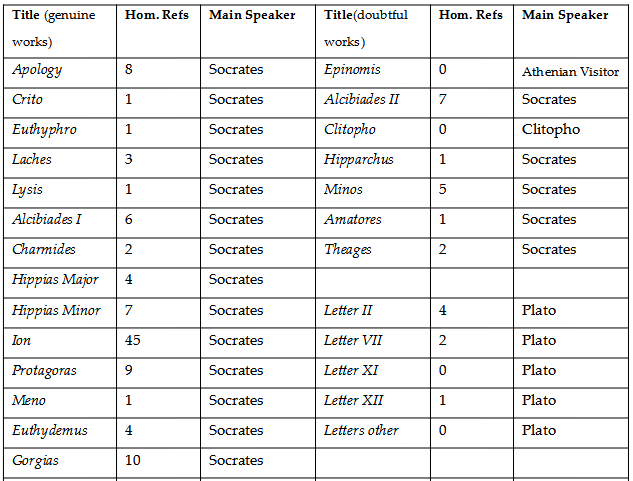

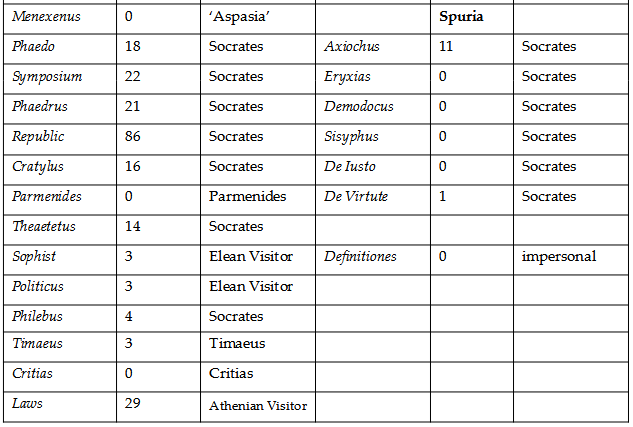

Socrates’ interest in Homeric poetry is evident in Plato’s dialogues. As can be seen on Table I below, out of 35 canonical Platonic dialogues, 30 of them contain Homeric references. They either mention Homer or his characters by name, or quote or refer to his poems as topics of discussion, sources of information or jokes, or function as ingredients of myth,1 and the majority of those references come out of Socrates’ own mouth. The fact that Socrates is not the main speaker of the five dialogues without Homeric references, namely Menexenus, Parmenides, Critias, Epinomis and Clitopho in which the main speakers are Aspasia, Permenides, Critias, Athenian Visitor and Clitopho respectively, makes Socrates’ frequent use of Homer even more conspicuous.2 This raises our curiosity as to whether the historical Socrates was also fond of Homer and could not help using Homeric references in his conversation, despite his famous criticism of Homer, especially in Republic.

One of the clearest statements of Socrates’ fondness for Homer is found in Republic X 595b9-10 where Socrates talks of his love (φιλία) and respect (αἰδώς) for Homer since his childhood, which makes him hesitate to criticise the poet and exile him from his ideal state. Even when Socrates banishes Homer from his ideal state (Republic X 607a), he acknowledges that Homer is a supreme poet (ποιητικώτατον 607a2) and goes on to use Homeric characters as the ingredients of his Myth of Er (Republic X 614b-621b) to conclude the dialogue. In the cases of Ion and Hippias Minor, he devotes the entire dialogues scrutinising the value of Homeric poetry as the tool of education while displaying a considerable knowledge of Homer, even outperforming the Homer experts, Ion and Hippias, respectively.

In Plato’s Apology, after he is condemned to death, Socrates can still look forward to the pleasure of conversing with Homer (41a7), Agamemnon and Odysseus (41c1) in the Underworld. Another striking example is Socrates’ dream reported in Crito 44a10-b3, in which a goddess-like figure3 talks to him with a Homeric line ‘ἤματί κεν τριτάτῳ Φθίην ἐρίβωλον ἵκοιο.’ (‘on the third day you should reach fertile Phthie.’). This is a modified quotation of Achilles’ word about his intention to go home at Iliad IX 363, with the final word changed from ἱκοίμην (I should) to ἵκοιο (you should). Socrates interprets the woman’s word as the prophecy of his death in three days’ time, as the death of his body will allow his soul, his true self, to return to its true home.4 If indeed he had such a dream, it is a remarkable testimony to the extent to which Homer occupied Socrates’ mind, including his subconscious. We may also note that in Phaedo 60d2 it is said that as he approached the end of his life, Socrates composed a hymn (προοίμιον) to Apollo, which indicates that he is capable of writing poems in hexameter.5

Xenophon’s Socrates

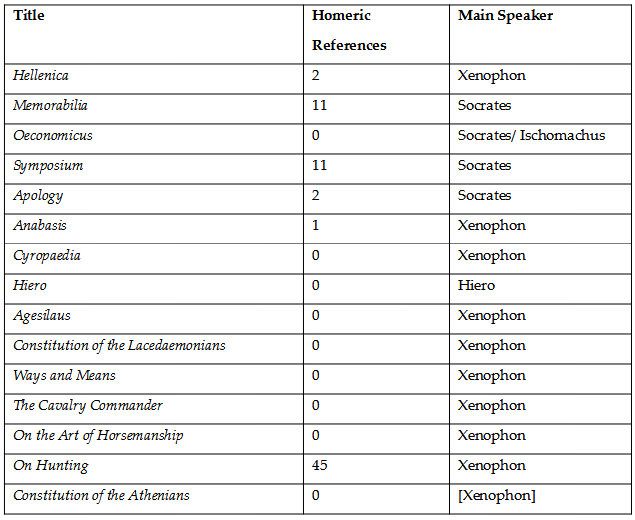

It is possible that the frequent references to Homer by Plato’s Socrates may reflect Plato’s love for Homer rather than Socrates’. However, we also have Xenophon’s testimony. As demonstrated by Yamagata (2012, pp. 138-140) and can be seen from Table II below, unlike Plato, Xenophon is usually sparing in his use of Homeric references in his writing, and yet his Socrates, too, uses Homeric references in the three of the Socratic dialogues which were written with the specific aim of producing faithful portrayal of Socrates (Apologia 1.1, Symposium 1.1, Memorabilia 4.8.11).

Only six out of fifteen works in Xenophon’s corpus contain Homeric references: Apology (2x: 26 Odysseus, 30 Homer gave power of prophecy to some dying heroes), Memorabilia (11x: spoken by Socrates: 1.2.58 (two quotes), 1.3.7-8 Circe turning greedy men into pigs, 2.6.11 the Sirens’ charm, 2.6.31 Scylla and the Sirens, 3.1.4 Agamemnon, 3.2.1-2 Agamemon, 3.5.10 Erechtheus, 4.2.10 Homer’s poems, 4.6.15 Odysseus; spoken by others: 1.4.3), Symposium (11x: spoken by Socrates: 3.6 criticises rhapsodes, 4.20 joking about the judgement of Paris, 8.23 Cheiron and Phoenix as examples, 8.30 (2 quotes) Ganymede, 8.31 Achilles and Patroclus; spoken by others: 1.16, 3.5, 4.6, 4.7, 4.45,), Hellenica (2x: 3.4.3, 7.1.34 both refer to Agesilaus’ attempt to emulate Agamemnon at Aulis), Anabasis (1x: 5.1 Leon of Thurii refers to Odyssey 18.75-118) and On Hunting (45x). The very large number in On Hunting is due to the mythical exemplars mentioned in the introductory section (1.1-17), which on stylistic grounds is dated to the reign of Hadrian and therefore not considered to be written by Xenophon himself (Marchant and Bowersock, 1968, pp. xlii-xliii).

As many as ten out of eleven Homeric references in Memorabilia and five out of eleven in Symposium are put in the mouth of Socrates (Yamagata, 2012, p. 140 and p. 142). Most strikingly Xenophon reports that Socrates’ ‘accuser’ (ὁ κατήγορος) said that Socrates had often quoted a particular passage from Homer (1.2.58, quoting Il. II.188-91 and 198-202). As in Plato’s dialogues, Xenophon’s Socrates frequently uses Homeric references as topics of discussion, or sources of information or jokes, though the myth-making using Homeric elements is confined to Plato’s Socrates. From this Yamagata (2012) concluded that the historical Socrates probably did use Homeric references frequently in his conversation, though the composition of myths featuring Homeric elements are likely to be ‘more Platonic than Socratic’ (p. 144).

Aristophanes’ Socrates

That conclusion appears convincing enough as far as the image of Socrates in Plato and Xenophon are concerned. However, if the frequent use of Homer in his conversation was such a prominent feature of Socrates, we may wonder why he does not quote or mention Homer in Aristophanes’ Clouds.6 Our response to that question might be that it is because Aristophanes was using the figure of Socrates to create a caricature of the intellectuals of his day, rather than painting a faithful portrait of how the man actually was (Dover, 1968, p. xxxiii; Graham, 1996, 197, n. 9). After all there are other aspects of Socrates in this play that do not appear to match up with Plato and Xenophon’s Socrates, such as providing lessons in an established school, apparently charging fees, instead of talking to anyone in public places with no money involved.

This apparent lack of Homeric references coming out of the sophist-like Socrates may tally with the Platonic data that there are fewer Homeric references in Plato’s dialogues in which a sophistic character is a leading speaker, such as in Parmenides with Parmenides as the main speaker (no Homeric reference), Sophist and Politicus in which the ‘Elean Visitor’ is the main speaker (three Homeric references each), whereas Socrates-led dialogues can feature Homer more frequently (e.g. Republic 86, Ion 45, Symposium 22, Phaedrus 22) (Table I). On the other hand, as is often pointed out, the caricature or parody of the subject does not work unless it has recognisable resemblance to the original. If the real Socrates was in the habit of frequently using Homer in his conversation to the extent that it was regarded as his ‘signature’, as it were, we need to consider why Aristophanes did not make him do so. Or did he?

Prompted by this question, I have re-read the play specifically searching for Homeric elements, and I believe I have found some. Although Socrates does not quote exact passages from Homer, he does use several expressions which can be regarded as Homeric in his invocation of the Clouds (269-274; tr. Sommerstein, 1991):

ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ

ἔλθετε δῆτ’, ὦ πολυτίμητοι Νεφέλαι, τῷδ’ εἰς ἐπίδειξιν

εἴτ’ ἐπ’ Ὀλύμπου κορυφαῖς ἱεραῖς χιονοβλήτοισι κάθησθε,

εἴτ’ Ὠκεανοῦ πατρὸς ἐν κήποις ἱερὸν χορὸν ἵστατε Νύμφαις,

εἴτ’ ἄρα Νείλου προχοαῖς ὑπάτων χρυσέαις ἀρύτεσθε πρόχοισιν,

ἢ Μαιῶτιν λίμνην ἔχετ’, ἢ σκόπελον νιφόεντα Μίμαντος·

ὑπακούσατε δεξάμεναι θυσίαν καὶ τοῖς ἱεροῖσι χαρεῖσαι.

SOCRATES

Yea, most glorious Clouds, come to display yourselves to this man:

whether ye now sit on the holy snow-clad peaks of Olympus,

or call the Nymphs to a holy dance in the gardens of father Ocean;

or whether again at the mouths of the Nile yet draw of its waters

with golden ewers,

or haunt Lake Maeotis or the snowy crag of Mimas:

hearken to me, accepting my sacrifice and rejoicing in these holy

rites.

This is arguably the part of the play in which Socrates speaks in the least sophistic manner, without philosophical argument. In this scene he is invoking the Clouds whom he worships as new deities. He lists a choice of possible locations of the goddesses, indicated with ‘whether… or…’ (εἴτε… εἴτε … εἴτε… in 270, 271 and 272 and ἤ… ἤ … in 273), which are found in prayers both in Homer and in general.7 Sommerstein (1991) compares this passage to Glaucus’ prayer to Apollo at Il. XVI.514-516 (tr. Verity 2011):

κλῦθι, ἄναξ, ὅς που Λυκίης ἐν πίονι δήμῳ

εἲς ἢ ἐνὶ Τροίῃ· δύνασαι δὲ σὺ παντοσ’ ἀκούειν

ἀενέρι κηδομένῳ, ὡς νῦν ἐμὲ κῆδος ἱκάνει.

Hear me, my lord, you who are somewhere in the rich land

of Lycia, or in Troy! Wherever you are, you are able to hear

a man in torment, as now torment has come over me;

The expression Ὀλύμπου κορυφαῖς (‘peaks of Olympus’ 270) also appears three times in Homer in the singular form κορυφῇ … Οὐλύμποιο (Il. I.499, V.754, VIII.3). The epithet χιονοβλήτοισι (‘snow-clad’ 270) does not appear in Homer in this form, but there are two occurrences of formulae denoting ‘snow-clad Olympus’ using synonymous epithets, namely Ὄλυμπον ἀγάννιφον in Il. XVIII.186 and Οὐλύμπου νιφόεντος in Il. XVIII.616. Moreover, Aristophanes’ Socrates uses the latter in its accusative form νιφόεντα in line 273 as the epithet of another mountain, i.e. Mt. Mimas. It seems evident that this passage is heavily indebted to Homer’s description of Olympus.

The concept of Ὠκεανοῦ πατρός (‘father Ocean’) in 271 also features in Homer as the progenitor of all the gods at Il. XIV.201, Ὠκεανόν τε, θεών γένεσιν, καὶ μητέρα Τηθύν (‘Oceanus, first father of the gods, and their mother Tethys’; tr. Verity 2011). Incidentally Plato makes Socrates quote this Homeric line in full in Theaetetus 152e7, bringing the images of the two versions of Socrates, Aristophanes’ and Plato’s, closer.

προχοαῖς (‘mouths of a river’) in 272 is also a Homeric word, occurring at Il. XVII.263, Od. 5.453, 11.242 and 20.65,8 the last of which refers to the mouths of Oceanus (προχοῇς ... Ὠκεανοῖο). προχοῇς appears in the same number and case in its Attic form προχοαῖς in 272, and Oceanus occurs in the line just above (271) in Socrates’ invocation. Rather like the case of the epithet ‘snow-clad’ transferred from Olympus to another mountain, this may be a case of a Homeric word transferred from Oceanus to another river.

Looking at the invocation as a whole, there is another possible echo in Plato’s Phaedrus, where Socrates playfully invokes the Muses before composing his speech on love (237a7-b1; tr. Rowe 1988):9

Ἄγετε δή, ὦ Μοῦσαι, εἴτε δἰ ᾠδῆς εἶδος λίγειαι, εἴτε διὰ γένος μουσικὸν τὸ

Λιγύων ταύτην ἔσχετ’ ἐπωνυμίαν, “ξύμ μοι λάβεσθε” τοῦ μύθου, ὅν με

ἀναγκάζει ὁ βέλτιστος οὑτοσὶ λέγειν, ἵν’ ὁ ἑταῖρος αὐτοῦ, καὶ πρότερον

δοκῶν τούτῳ σοφὸς εἶναι, νῦν ἔτι μᾶλλον δόξῃ.

Come then, you Muses, clear-voiced (ligeiai), whether you are called that from

the nature of your song, or whether you acquired this name because of the

musical race of the Ligurians, ‘take part with me’ in the story which this

excellent fellow here forces me to tell, so that his friend, who seemed to him to

be wise even before, may seem even more so

now.

Here is the same pattern of ‘whether… or…’ (εἴτε… εἴτε…), and the invocation of the Muses is reminiscent of poets, especially Homer.10 Socrates also jokingly speaks of invoking the Muses in Plato’s Euthydemus (275c-d) and Republic (VIII 545-e), and unspecified ‘gods’ in Timaeus (27c) (Capra, 2014, p. 44, n. 69). It makes one wonder whether Plato was influenced by Aristophanes’ Clouds passage or the real Socrates did often invoke the Muses or other deities poetically like this before his important speeches, or both. Moore (2015, pp. 545-551) convincingly demonstrates how Plato’s Phaedrus constantly alludes to Aristophanes’ Clouds. It is perfectly possible that in this passage, too, Plato is reacting to Aristophanes’ portrayal of Socrates.11

The context in which Socrates’ invocation of the Clouds occurs is also significant in considering its style. The charm of this ‘Homeric’ invocation has been praised for its remarkable lyricism, figurative language (such as the golden pitchers), poetic words (such as προχοή and νιφόεις), and ‘a majestic rhythm’ (Fisher, 1984, pp. 88-89). However, it has often been overshadowed by the parodos of the Chorus of Clouds thus invoked (275-290, 300-313), which has received much more critical attention and praise. Segal (1969) famously called it ‘one of the most beautiful lyrical passages of Attic literature’ (p. 169), with its mainly dactylic, dignified, metre.12 We should rather give credit to Socrates’ invocation for inducing the Chorus to sing the elevated song in response to his Homeric poetry. Here we find again, as seen in Plato, the image of Socrates who is fond of Homer and capable of creating a ‘Homeric’ conversation with heavenly beings who duly respond to him with ‘dactylic’ verse.

To be sure, Socrates’ ‘Homeric’ prayer in the Clouds is ‘mock-heroic’, out of place in the comic context,13 and is a parody as much as his sophist-like persona in the rest of the play. Marianetti (1993) sees a parody of the initiation of the Eleusinian Mysteries in the ‘initiation’ scene (254-260) in the Clouds (p. 16). Moreover, Socrates’ action of summoning the Clouds itself puts him in the position of the ‘Cloud-Gatherer’ (νεφεληγερέτα), one of the epithets of Zeus in Homer. In discussing why Clouds make up the chorus for the play, Konstan (2011) explains, ‘They represent the comic Socrates’ interest in meteorology, of course; they serve too as nature deities, like the Vortex which, as Socrates will late explain, has replaced Zeus as the chief divinity in the physicists’ pantheon… For it is basic to the characterization of Socrates in Clouds that he is passionately interested in cosmology.’ (p. 78). To this we may add that Socrates is also passionately interested in Homer and therefore making him a ‘Cloud-Gatherer’ creates a particularly biting satire of the Homer-loving Socrates, who denies the existence of Zeus (367) and usurps the god’s function. All of this might have fuelled the accusation of blasphemy at Socrates’ trial.

We must also take into account that Clouds is not the only play by Aristophanes that features Socrates. As Capra (2018, pp. 64-65) points out, the playwright’s references to Socrates span over a quarter of a century. Socrates is mentioned in Birds (1282, 1555), Frogs (1491) and possibly in his first play Banquetteers, too (Capra, 2018, p. 64), indicating Aristophanes’ interest in and knowledge of the philosopher. There is a passage which places Socrates in a Homeric context in the Chorus’ song at Birds 1553-1564 (tr. Henderson, 2000):

πρὸς δὲ τοῖς Σκιάποσιν λίμνη

τις ἔστ᾿, ἄλουτος οὗ

1555 ψυχαγωγεῖ Σωκράτης.

ἔνθα καὶ Πείσανδρος ἦλθε

δεόμενος ψυχὴν ἰδεῖν ἣ

ζῶντ᾿ ἐκεῖνον προὔλιπε,

σφάγι᾿ ἔχων κάμηλον ἀμνόν

1560 τιν᾿, ἧς λαιμοὺς τεμὼν

ὥσπερ οὑδυσσεὺς ἀπῆλθε,

κᾆτ᾿ ἀνῆλθ᾿ αὐτῷ κάτωθεν

πρὸς τὸ λαῖμα τῆς καμήλου

Χαιρεφῶν ἡ νυκτερίς.

Far away by the Shadefoots

lies a swamp, where all unwashed

1555 Socrates conjures spirits.

Pisander paid a visit there,

asking to see the spirit

that deserted him in life.

For sacrifice he brought a baby

1560 camel and cut its throat,

like Odysseus, then backed off;

and up from below arose to him,

drawn by the camel’s gore,

Chaerephon the bat.

It has been pointed out that this is a parody of ‘Nekyia’ in Odyssey Book 11 and also influenced by Aeschylus’ play Psychagogoi (Ψυχαγωγοί) which is itself based on Od. 11.14 The reference to Odysseus in line 1561 certainly points to his action in Odyssey 11.35, except that the sacrificial victim here is a camel (κάμηλον) instead of sheep (μῆλα). The references to the psychagogos in 1555 and the bat in 1564, however, seem to evoke the ‘second Nekyia’ in Od. 24, where Hermesleads (ἄγε, 5) the souls (ψυχάς, 1) of the suitors into Hades and they are described with a simile of bats (24.6-9). This passage can therefore be seen as another example from Aristophanes’ play in which Socrates is playing the part of a divine figure in a mock-Homeric scene, here acting as a psychagogos (or Psychopompos)15 to a bat-like character.16 This parallel seems to provide further support for the interpretation of Socrates’ role as the ‘Cloud-gatherer’ in the Clouds and Aristophanes’ intention to associate Socrates with Homer.

Despite all the parody and distortion, it is a fair assumption that we have in Clouds a portrait of Socrates ‘with all his idiosyncrasies’, as Nussbaum puts it (1980, p. 72), and this portrait partially overlaps with those painted by Plato and Xenophon, displaying his habit of using Homer in his conversation, sometimes seriously, sometimes jokingly and sometimes poetically. Moreover, we have credible evidence that Plato consciously responded to Aristophanes’ portrayal of Socrates in Clouds in his dialogues, including Phaedrus. The similarity of Socrates’ joking prayer to the Muses in Phaedrus to Socrates’ invocation of the Clouds in Aristophanes’ comedy makes it likely that they reflect some aspects of the real Socrates, which are recognisable through each mock-Homeric context. Along with Plato and Xenophon Aristophanes seems to provide us with additional evidence that the historic Socrates was a Homer-lover.

References

Ahbel-Rappe, S., and Kamtekar, R. (Ed.). (2006). A Companion to Socrates. Malden, MA. and Oxford: Blackwell.

Burnet, J. (Ed.). (1924). Plato. Euthyphro, Apology of Socrates and Crito. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bussanich, J. (2006). Socrates and Religious Experience. In Ahbel-Rappe and Kamtekar (Ed.). A Companion to Socrates (pp. 200-213). Malden, MA. and Oxford: Blackwell.

Capra, A. (2014). Plato’s Four Muses: The Phaedrus and the Poetics of Philosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: Harvard University Press.

Capra, A. (2018). Aristophanes’ Iconic Socrates. In Stavru and Moore (Ed.), Socrates and the Socratic Dialogue (pp. 64-83). Leiden: Brill.

de Fátima Silva, M., Bouvier, D. and das Graças Augusto, M. (Ed.) (2020). A Special Model of Classical Reception: Summaries and Short Narratives. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

de Luise, F. and Stavru, A. (Ed.). (2013). Socratica III: Studies on Socrates, the Socratics, and the Ancient Socratic Literature. Sankt Augustin: Academia Verlag.

Dover, K. J. (1968). Aristophanes Clouds edited with Introduction and Commentary. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

Dunbar, N. (Ed.) (1995). Aristophanes Birds edited with Introduction and Commentary. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press.

Fisher, R. K. (1984). Aristophanes Clouds: Purpose and Technique. Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert.

Graham, D. W. (1996). Socrates and Plato. In Prior (Ed.), Socrates: Critical Assessment (vol. ,1 pp. 179-201). London and New York: Routledge. (= Phronesis, 37 (1992), 141-165).

Hunter, R. (2012). Plato and the Traditions of Ancient Literature: The Silent Stream. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Konstan, D. (2011). Socrates in Aristophanes’ Clouds. In Morrison (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Socrates (pp. 75-90). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McPherran, M. (1996). The Religion of Socrates. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

McPherran, M. (2003). Socrates, Crito, and their debt to Asclepius. Ancient Philosophy, 33, 71-92.

Marchant, E. C., and Bowersock, G. W. (Ed.). (1968). Xenophon VII: Scripta Minora translated by E. C. Marchant, Pseudo-Xenophon Constitution of the Athenians translated by G. W. Bowersock. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: Harvard University Press.

Marianetti, M. C. (1993). Socratic Mystery-Parody and the Issue of ἀσεβεια in Aristophanes’ Clouds. SymbolaeOsloenses, 68, 5-31.

Mitchell, T. (1838). The Clouds of Aristophanes with Notes critical and explanatory, adapted to the use of schools and universities. London: John Murray.

Moore, C. (2013). Socrates Psychagogos (Birds 1555, Phaedrus 261a7). In de Luise and Stavru (Ed.), Socratica III: Studies on Socrates, the Socratics, and the Ancient Socratic Literature (pp. 41-55). Sankt Augustin: Academia Verlag.

Moore, C. (2015). Socrates and Self-Knowledge in Aristophanes’ Clouds. The Classical Quarterly, 65(2), 534-551.

Olson, S. D. (Ed.). (2014). Ancient Comedy and Reception: Essays in Honor of Jeffrey Henderson. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Olson, S. D. (2021). Aristophanes’ Clouds: A Commentary. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Platter, C. (2014). Plato’s Aristophanes. In Olson (Ed.), Ancient Comedy and Reception: Essays in Honor of Jeffrey Henderson (pp. 132-165). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Prior, W. (Ed.). (1996). Socrates: Critical Assessments Vol. I. London and New York: Routledge.

Rashed, M. (2009). Aristophanes and the Socrates of the Phaedo. Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, 36, 107-136.

Robson, J. (2009). Aristophanes: An Introduction. London: Duckworth.

Rowe, C. J. (Ed.) (1988). Plato: Phaedrus, with translation and commentary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Rowe, C. J. (Ed.) (1993). Plato Phaedo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ryan, P. (2012). Plato’s Phaedrus: A Commentary for Greek Readers. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Segal, C. (1996). Aristophanes’ Cloud-Chorus. In Segal (Ed.), Oxford Readings in Aristophanes (pp. 162-181). Oxford: Oxford University Press (= Arethusa, 2, 143-161).

Segal, E. (Ed.). (1996). Oxford Readings in Aristophanes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Silk, M. (1980). Aristophanes as a Lyric Poet. Yale Classical Studies, 26, 99-151.

Silk, M. (2000). Aristophanes and the Definition of Comedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sommerstein, A. H. (Ed.) (1991). The Comedies of Aristophanes: Vol. 3: Clouds, edited with an Introduction, translation and Notes (3rd corrected impression). Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Sommerstein, A. H. (Ed.) (2008). Aeschylus Fragments, edited and translated. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press.

Stavru, A. and Moore, C. (Ed.) (2018). Socrates and the Socratic Dialogue. Leiden: Brill.

Tarrant, D. (1951). Plato’s Use of Quotations and Other Illustrative Material. The Classical Quarterly New Series, 1(1-2), 59-67.

Van Leeuwen, J. (1968). Aristophanes Nubes: cum prolegomenis et commentariis edidit (Editio secunda). Leiden: A. W. Sijthoff.

Verity, A. (Tr.) (2011). Homer: The Iliad, Translated by Anthony Verity with an Introduction and Notes by Barbara Graziosi. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yamagata, N. (2012). Use of Homeric References in Plato and Xenophon. The Classical Quarterly New Series, 62(1), 130-144.

Yamagata, N. (2020). Homeric Summaries in Plato. In de Fátima Silva, Bouvier and das Graças Augusto (Ed.), A Special Model of Classical Reception: Summaries and Short Narratives (pp. 22-33). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Notes

Recepción: 01 Febrero 2022

Aprobación: 15 Marzo 2022

Publicación: 01 Abril 2022